LaVergne in France during the War.

LaVergne in France during the War. 2008

2008*from Housman's poem With Rue My Heart Is Laden

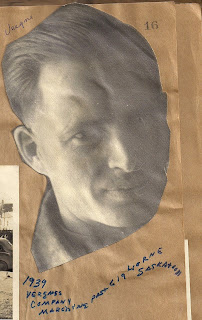

When I was twelve, freckled and awkward, all the aunts and uncles seemed glamorous as movie stars, sophisticated with their cigarettes and glasses of amber liquid and tinkling ice cubes. But the uncle I admired most was LaVergne, tall, handsome, gallant. His grand name suited his thin moustache, Clark Gable looks and dreamy, faraway eyes.

He was my Ideal Man. I have never met another that measured up to his example.

The oldest of my grandma's five children, he was raised through the Depression. When he left home to make his own way, my grandparents took him to the train station. "I'll never forget seeing him off," my grandma told me. "All we could give him was ten dollars. That's all he had to make his way in the world."

He worked his way over to England on a freighter. When World War II broke out, he joined the RAF, eventually becoming an officer. There is a photograph in one of our old family albums of him as a flag-bearer, on bended knee before the Queen, during a presentation. In that same scrapbook, photos of Greta, his future wife, appeared, with the words "the most beautiful girl in the world" written in his elegant script under the picture of her piquant face. On one of his trips home, they were married.

He was dashing in uniform, as you can see, his handsome face smiling out with brave and steady eyes. He sent home a piece he wrote about landing in Sicily, walking through vineyards, picking grapes. "Dusty, but that can be washed off," he wrote. The only thing he wrote about the war, and war was no where in it. He returned home partially deaf from gunfire. He never spoke of the things he saw there, but I could tell it hurt his heart to have witnessed such raw suffering.

My uncle was a romantic, with a dreamy, thoughtful, introspective nature. He enjoyed watching, didn't need to be the center of attention.

Through the war, his wife Greta waited for him with their infant daughter, Jeanette. Greta was his match in movie star glamour. She was thin with a pretty face and short curled hair. "Vergne called their family, with satisfaction, "The Three Bears." "Ready to go, Mama Bear?" he'd ask. He adored her, was utterly attentive to her. All Greta had to do was take a cigarette out of the package, and he'd leap across the room to light it for her, her gallant knight to the end of his days.

The three of them lived nost of their marriage in Saskatoon, where my grandparents had raised their family. When LaVergne was in his forties, we heard he was having trouble with his legs. For a time, they feared MS, and he visited Mayo Clinic. Luckily it wasn't MS, but I never did find out what the trouble was. Grandma told me that sometimes Greta would find him downstairs in the family room crying from the pain.

There was talk in the family that the company he had devoted his career to had treated him badly. He was bitterly disappointed. He had such ethics, did his best, could not fathom that being returned with unfairness. Plus he felt shamed by their financial downturn. They had to sell their big house, and Greta was not happy. Their lives had been Technicolor perfect. She was not accustomed to hard times, not up to life in the trenches. We felt she blamed him.

My grandparents had moved to Kelowna in the '40's. When my grandfather was dying, in the '70's, my sister and I caught the bus to be with him, and it was LaVergne who met us at the bus depot. He put his arm around me, smiling kindly as he looked down at me. "He couldn't wait for you," he said. "He's gone." He had suffered a cerebral hemhorrage.

The family was most concerned about how my grandma would manage after his death. She had never been alone, never written out a cheque or paid a bill. LaVergne and Greta moved from Saskatoon to live near her. My uncle started a business as an accountant and they white-knuckled it, hoping it would succeed.

My uncle dropped by my grandma's apartment faithfully twice a day. "He gave me hugs," my grandma told me later. "He was always smiling, always cheerful, and he cared how I was feeling. My friend told me later that she would see him on the street and he would be limping, his legs were in so much pain. But he hid that from me, he never complained - about anything - so I didn't know he was suffering."

Greta had not taken the move to Kelowna well. They had a small cottage on the outskirts, looking out on dry brown hills. She mourned her big house, her life in Saskatoon. She missed their daughter who was raising the grandbabies so far away from her. And the business was not doing well. She was visibly unhappy. LaVergne's eyes were stricken and sad. Mama Bear was unsmiling and Papa Bear couldn't make things right. The fairy tale was ending sadly and he felt less of a man because of it. I think he felt he had let Greta down.

But the family felt she had let him down by not loving him through the hard times. His eyes betrayed his disappointment, his understanding that her love was conditional. He kept on smiling, doing the best he could. There were whispers he was drinking more than usual. But he was an elegant man who never lost control of himself. He would never allow himself to not meet his own high standards for civilized behavior. I never saw him to be anything but dignified.

One night Greta heard a thump and found him lying on the floor in the living room. Unthinkably, by the time the ambulance came, he was dead, just eighteen months after my grandfather. He had phlebitis, and a blood clot in his leg had broken loose.

I remember my grandma's stoicism at the funeral, as she sprinkled holy water on the casket, standing beside me as strong as an oak tree, blessing his coffin as if with leaves. She didn't shed a tear, but her mourning doubled. She carried it silently with her for the rest of her life.

The family muttered about how Greta had let him down in his last years, how she should have known he was in such distress. But grandma would hear none of it. "He loved her," she said firmly. And that was the end of it.

Greta moved back to Saskatoon, to be near her daughter. Some years later she died of cancer.

When I remember my gallant uncle, I recall him in his glory years, tramping the hills with his big black dog Smoke, or leaping across the room with a flourish to light his beautiful wife's cigarette. So happy to have the woman he adored as his wife.

He was gallant, a romantic figure, with a wistful look in his eyes I recognized. I imagine him, handsome, tall and slender, leaning back against a fence, ankles crossed. And those smiling eyes lighting up when Greta arrived in the spirit world. That secret half-smile he reserved just for her, his hand reaching out.

"Ready to go, Mama Bear? Been waiting for you."

I love this story, Sherry! How lucky you are to have people and memories like that in your life. Your uncle was a charmer indeed!

ReplyDeleteWhat a great photo..such regal bearing, and those wonderful eyes. It's a vivid and lovely picture you painted of him waiting in the spirit world for his beloved wife...

No wonder few men you've met since have measured up to his standard! Sigh...a most satisfying read altogether...

Thanks, Lynette. So glad you enjoyed it. I did admire him so much, he was a class act. Do you remember who penned the lines in the title? Even Jeeves on Google doesnt seem to know......it escapes me...........and I need to give the author credit!

ReplyDeleteWhat an amazing man; I wish I had an

ReplyDeleteUncle like him. The uncle that I think would come close, died of

Leukemia when I was 10yrs old. He

struggled so, but kept on being a man of respect! He is so handsome and has an endearing quality! Some people truly come into our hearts and leave footprints on our soul!

He was unique...I loved how you painted him. Your writing flows and I wanted to hear more...

Great post~

Thank you, Ellie. It makes me happy that you are following my posts.....never fear, THERE WILL BE MORE, hee hee.......it must have been hard for you when your uncle died, since you were so young. He sounds brave. My son is going thru chemo right now. It amazes me every time we go to the oncology ward, just how positive everyone is. People are very brave.

ReplyDeleteHi Sherry:

ReplyDeleteI expect you remember the phrase from a toast in 'Out of Africa'. It is from the poem, 'Shropshire Lads' by A.E. Housman...

"With rue my heart is laden

For golden friends I had,

For many a rose-lipt maiden

And many a lightfoot lad.

By brooks too broad for leaping

The lightfoot boys are laid;

The rose-lipt girls are sleeping

In fields where roses fade.

It is the perfect title for this post!

Lynette

I somehow THOUGHT it was Housman, and was thinking of that poem from Out of Africa......my subconscious remembered, but it was too long a journey to get to my brain, hee hee. Thank you....will rectify it.......I just cropped my grandparents photo and reposted it and am very proud of myself!

ReplyDeleteWonderful story, beautifully told.

ReplyDelete